Don Paquale

|

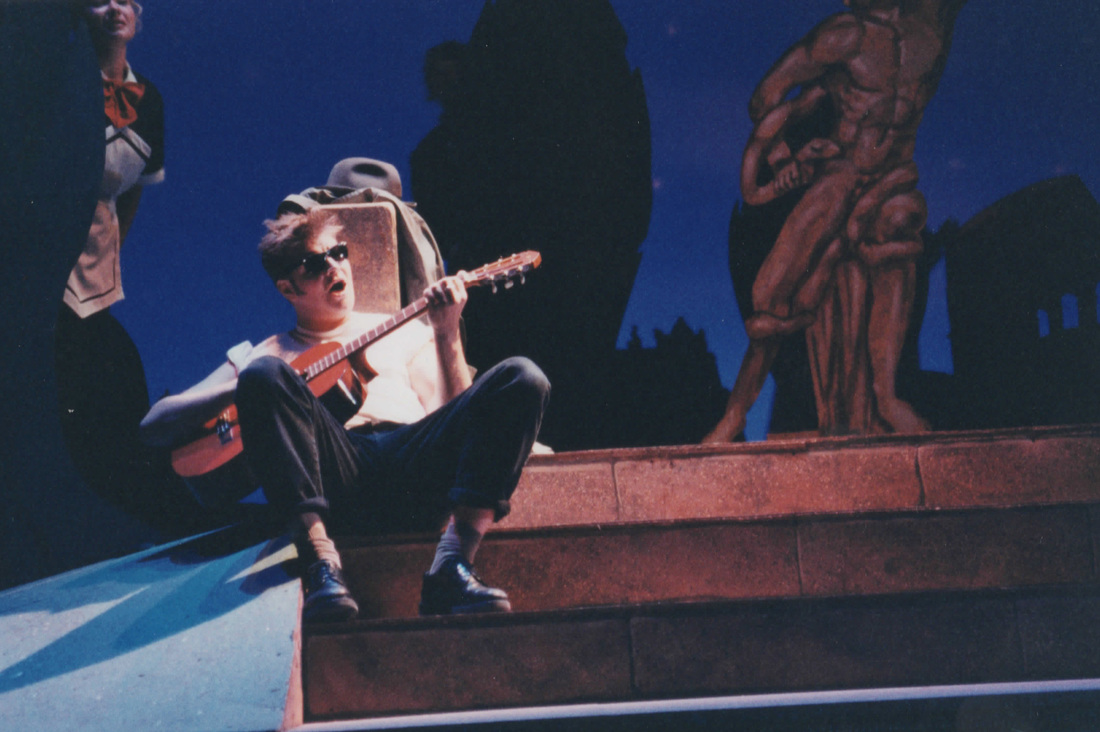

West Bay Bumps 'Don Pasquale' into the 1950s

By Philip Collins 10.16.97 Who would have thought that a comic opera about a lecherous old geezer getting his comeuppance would elevate Gaetano Donizetti’s already illustrious career to new heights? It’s not like the territory hadn’t been turned over countless times by 1842. Actually, the producers at the Théâtre-Italien in Paris were notably unimpressed by Don Pasquale prior to the work’s hugely successful opening. The composer knew better: he’d predicted a hit all along. West Bay Opera’s current production of Don Pasquale at the Lucie Stern Theater in Palo Alto got the company’s 42nd season off to a romping good start. Friday’s cast, which alternates every other performance with a second ensemble, gave an over-the-top performance that included some gorgeous singing. Director Yefim Maizel brought out the sheer playfulness of Donizetti and librettist Giovanni Ruffini’s three-act buffa. The singers relished their assignments, and the audience shared in their delight, laughing when it counted and applauding heartily after the featured arias. There is a pathetic quality to Don Pasquale in that every laugh is made at the expense of the title character—poor old fellow. His nephew Ernesto wants to wed the indigent widow Norina rather than accept an arranged marriage. Pasquale disinherits Ernesto and then, with the aid of his friend Dr. Malatesta, embarks upon his own ruse to marry the doctor’s younger sister, who happens to be none other than Norina in disguise. Dr. Malatesta, sympathetic to his sister’s and Ernesto’s plight, constructs a bogus wedding ceremony between Pasquale and Norina, after which the young ingenue transforms into a raging shrew. Following a binge of outrageous shopping sprees, a staged affair and some serious haranguing, Pasquale begs off for bachelor life and even blesses his nephew’s marriage to Norina. Maizel’s central dramatic conceit in Don Pasquale is setting the action in the 1950s rather than 1840s. It is a viable idea that unfortunately barely gets fleshed out. Aside from some of Robyn Spencer-Crompton’s wonderfully garish period costuming and set designer Jean-Francois Revon’s exquisite ‘50s kitsch furniture in the third act that sets the tone for the show’s zany finale, the production remains quite cozy in 19th-century digs. As the pining nephew Ernesto, tenor Thayer Coburn was the best equipped to milk the ‘50s aura. Coburn played the part with shades, leather and a touch of poutiness—the King does Donizetti. Maizel’s idea to give Ernesto a trumpet and have him mime the plaintive trumpet solos while sprawled out on the couch was truly inspired. Coburn's understated performance was a breath of fresh air compared to the trite and overworked gimmicks of the other principals. There were more muggings during the overture—which featured a pantomimed tableau with the curtain down—than in an entire weekend in Manhattan. Baritone Douglas Nagel anchored the production vocally in the title role, bringing a wealth of shadings to Pasquale’s brooding part, and his delivery of the temper tantrum in Act III was wild. Unfortunately, grimacing and character ticks were applied so liberally during the first two acts that the facial nuances Nagel introduced in the final scenes had negligible impact. Sharon Maxwell’s poised performance as Norina managed, if not championed, the role’s daunting vocal gymnastics without attending to even the most straightforward cases of diction. Her vocalizing of the opening cavatina, “Glances so soft,” was lovely, but the specifics of Phyllis Mead’s translation were anybody’s guess. The pronunciation was so consistently un-negotiated by most of the cast that supertitles would have been a blessing during many of the scenes. The West Bay Opera Chorus turned in some of its finest singing, and Maizel’s diverse stagings of them amid scenic props worked hilariously. If earlier scenes had been as well crafted interpretation the first hour would’ve proved endlessly more gratifying. Hurrah for the musicians in the pit, who under Henry Mollicone’s direction contributed many delicious episodes. The ensemble singing was sturdy and well balanced. The quartet ending Act II built smoothly and gelled particularly well. Although Norina and Ernesto’s nocturne in the third act was not much for vocal blend, the orchestra’s gentle assist exuded Donizetti’s fondness for Mozart. |